By: Michael Useem, Director, Center for Leadership and Change Management at the Wharton School of Business

We seek as a result to focus attention on building more engaged leadership in the boardroom, not just the executive suite. Governing boards should take more active leadership of the organization, whether a corporation, hospital, or museum, not just monitor its management. We expand the working concept of governance from one of arms-length oversight to trustee leadership of the most strategic decisions.

Rather than being concerned with whether trustees should serve staggered or limited terms, we worry more about whether the chair can help direct the board in guiding strategy, setting the ethical tone, and gauging risk in concert with the chief executive, and whether the trustees’ talent and collective chemistry make the board a substantive player at the table. This calls for a different kind of vigilance in the boardroom, a deeper kind of relationship between trustees and executives, and a new kind of leadership from both.

The emerging governance model is a result of forces not of its own making. In the private sector, increased regulation, ownership pressures, and governance reforms over the past decade have been intended to strengthen the board’s oversight function. Yet as boards have become better monitors, they have also become better leaders, delving into a host of other areas that had been delegated to top management in earlier times.

We believe that directors in the private sector and trustees in the non-profit community can and will more actively lead in the years ahead, and on balance we anticipate that this should fortify their organization’s success and performance. But that is not a given. Poorly handled, this new enablement can cause serious damage, resulting in fractured authority and dangerous meddling.

A New Model of Collaborative Leadership

In a 2002 letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, Warren Buffett lamented his multiple derelictions of duty as a director of some forty corporations over nearly two decades: “Too often I was silent when management made proposals that I judged to be counter to the interest of shareholders,” Buffett wrote. “In those cases, collegiality trumped independence [and a] certain social atmosphere presides in boardrooms where it becomes impolitic to challenge the chief executive.”

A decade later, biopharmaceutical Amgen Inc. CEO Kevin Sharer painted an almost opposite picture of the relationship between the governing body and corner office: “You’re a lion tamer and they’re the lions. Respect them, but if you let them eat you, they will. Working with the board is vital, complex, and beyond your prior experience—unlike anything you’ve done before. It is among the most complex human relationships, especially if you’re the chair, when you’re their boss, and they’re your boss. Get the relationship right, or it will hurt you.”

Allow for a little hyperbole on both sides—Warren Buffett was never that neglectful, and Kevin Sharer carried neither whip nor chair to keep his directors at bay. Still, the difference between the two observations illustrates a striking reconfiguration taking place in how boards operate and how directors and trustees work with top management: the emergence, in an extraordinarily short time, of the potential for boards to be a vital partner and new force in governance.

But note the qualifier—potential. This leadership capacity has yet to be fully exploited or even realized at many firms. Too often, directors and trustees remain one of the most valuable but least utilized of an organization’s assets. Smart, experienced, and dedicated men and women are ready to serve. They are sworn to protect and advance the enterprise, to ensure that it does what is best for customers, investors, donors, and visitors. Yet their wisdom and guidance are still too often closeted in the boardroom.

But the prevailing model is changing, and quickly. At organization after organization, boards and management have been embracing new practices that help define a more directive, more collaborative leadership of the enterprise. They are jointly taking charge of strategic choices, merger decisions, risk tolerance, ethical climate, and other functions that have traditionally been the province of management.

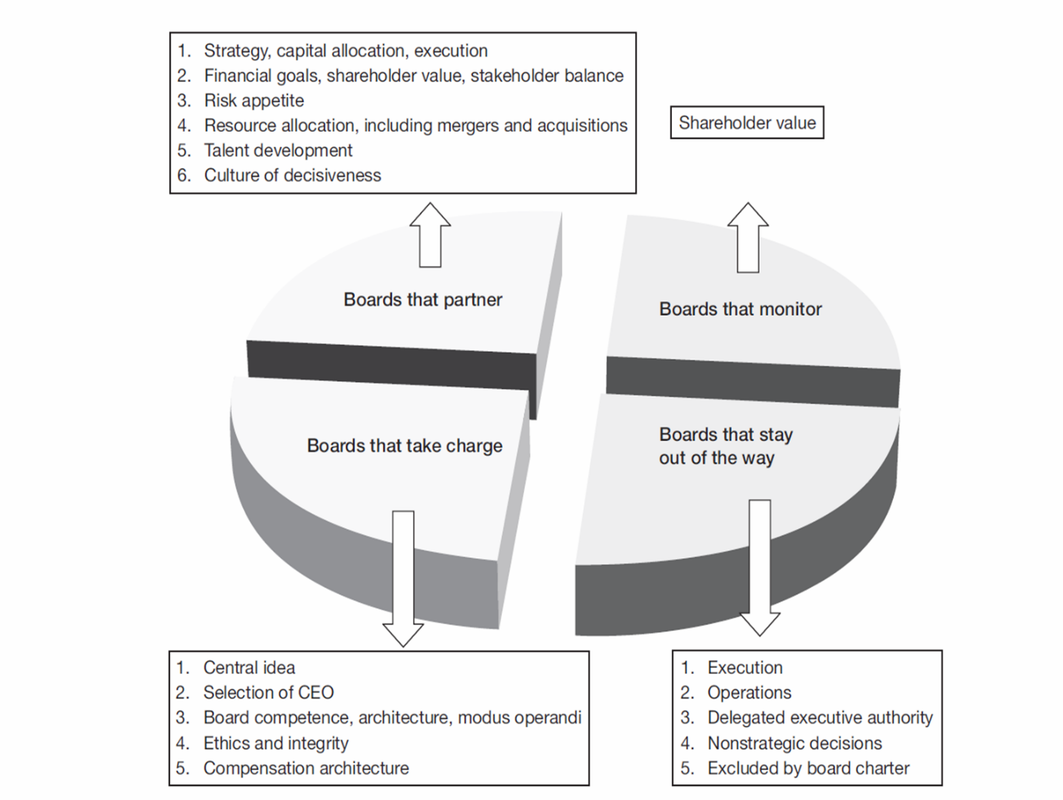

Boards That Monitor, Partner and Take Charge

Each board will want to fashion its own unique blend of the components of direct and collaborative leadership. “Boards should sit down” annually, urged Ford Motor Company’s lead director Irvine Hockaday, “and say, OK, what are we really doing here, what really is our role given the situation of this company at this time, what are we doing to incarnate that role, how are we going to function with the lead director, and what are our priorities?”

Finding the right balance among the board’s leadership components—knowing when to lead, when to partner, and when to stay out of the way—has become one of the premier tasks of the board’s leadership of any enterprise.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed